Will the Country Finally Admit That Personal Economics Is a Big Problem?

Too many politicians, economists, and pundits keep insisting everything is fine. It’s absolutely not.

Going into the election, Democratic leadership, pundits, and associated economists seems sadder than angry. They couldn’t understand why people thought the U.S. economy was doing badly. Number after number told these people that things were fine. Why couldn’t the complainers just listen and admit the truth?

Because it wasn’t and isn’t true. There is of the economy as a grand thing, with gross domestic product (GDP) growth still decent, inflation easing down toward the Federal Reserve’s magic 2% target, and labor, with some ups and downs, remaining strong. Then there is the personal experience of more than half the country, who can’t keep their heads above water without “transfers,” meaning government programs.

Some examples of the first: the advance estimate of gross domestic product — call it the economy for short — in the third quarter that ended September 30 was a 2.8% annualized real GDP. While the Q3 figure was a slight slowdown from the second quarter’s 3.0%, it’s nothing to sneeze at. The unemployment rate in October stayed at 4.1%. For those aren’t old enough to remember, rates at more than 5% used to be considered good. As for inflation, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index, the preferred measure of the Federal Reserve, hit 2.1% Goldman Sachs projected earlier in October. Given the rate at which inflation has been dropping, hitting 2% should happen in the immediate future.

With growth continued, the labor market where it seems to be, and inflation falling, this seems like the definition of a so-called soft landing.

Mary C. Daly, president and chief executive officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, said in a recent speech that it’s necessary to look beyond a soft landing to see what is needed going forward.

“Recalibrating policy,” the phrase that Daly used, should be clear as a concept, though it goes beyond monetary theory. Both the Fed and the federal government reacted strongly across the stretch of the COVID-19 pandemic. Congress pulled back on fiscal actions, but it has taken the Fed longer. The latter’s decision of what is now normal is more complicated.

High inflation took a big bite out of the “real incomes and purchasing power” of all Americans, as Daly noted, particularly those in the lower half to 60% of the economic stratum. Even as the rate of inflation has lowered, the prices of things in general have increased.

Guess what? Prices won’t drop. Mohamed El-Erian, president of Queens' College, Cambridge; chief economic adviser at Allianz SE; chair of Gramercy Fund Management; and former chief executive officer of Pimco, a giant in fixed income investments, was asked by Face the Nation's Margaret Brennan, “For average people, they see housing prices are high, they see grocery prices are still high, where's the scenario where those prices actually come down.”

He smiled for a moment and then said, "Yeah, and that's what everyone's expecting, but it's not going to happen. Look, the good news is interest rates will continue to come down. The good news is inflation, which is the rate of increase of the cost of living, will come down. But it's very hard to bring down prices. And that's one political problem. When you tell people inflation's coming down, in their head, they think prices are coming down, not the rate of increase of prices. So, it's a misunderstanding, unfortunately, but you've got to be careful what you wish for because if prices come down significantly, we are then in something much worse economically."

He was referring to deflation, where there is a spiral of pricing dropping, people waiting for them to drop more, companies trying to entice buying by further lowering prices, and then come the layoffs and a falling economy. It hasn’t happened in close to 100 years, but the last time it did, the U.S. had the Great Depression. That prospect scares people in economics through and through.

Higher established prices from inflation — yes, corporate greed, but many other complex factors as well — have put ever more pressure on the lower end of the economic scale. People who on the whole are poorer than those who are wealthier are getting clobbered. The graph below uses data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta through the St. Louis Fed’s site. The data shows nominal wage growth (without considering inflation) of the 25th percentile, 75th percentile, and median. Then inflation was for a sense of how people are doing with an estimate of real (after inflation) wage growth.

Take a close look at that zero line, the demarcation point at which you go from growth to no significant change to loss.

The assumption that inflation hits everyone equally is wrong. If you have higher education or medical bills, you’re hit harder. Your housing costs have risen faster than the overall inflation number if you rent, though if you own your home with a low mortgage rate, you’re in far better shape. How will the economy help put people back together? It won’t left to its own devices.

As Daly said in her speech, “[T]he burden fell particularly hard on low- and moderate-income families, who spend a disproportionate share of their resources on shelter, food, and fuel, where price increases have been especially large.” Right, and that means more than half the country.

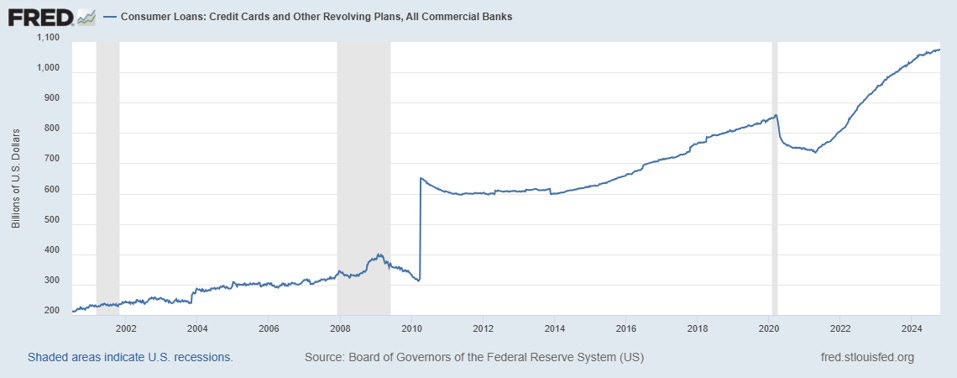

Now, on to interest rates, which affect consumers and businesses of all sizes, although not equally. Again, consumers are at historically high uses of credit as the graph below shows.

That’s not necessarily a problem unless real income hasn’t kept up. For more than half the country, it hasn’t.

Don’t expect interest rates to return to the ultra-low levels they occupied for about 15 years since the Great Recession. From a view of monetary theory, if the economy is growing, the labor market is strong, and inflation is falling, there doesn’t seem to be a reason to keep lowering interest rates. The country may be back to how the economy worked for many years before the entire housing market blew apart in 2008 and 2009 because of gross systemic mismanagement and greed.

Daly said, “The expansion just prior to the pandemic was especially impressive: nearly 11 years, 10 years and 8 months to be precise, the longest on record.”

Yes, and that was after the entire global economy took a nosedive and the U.S. economy one took at least a decade to get back to where it had been. In had a long way to crawl back. But if things are starting to look like pre-pandemic times, expecting roaring prosperity, at least below the upper quarter, might not be realistic.

Some might point out that I haven’t added the value of transfers, economic jargon for all the programs that pump money through the government into those who are struggling. But, for heaven’s sake, the people receiving it don’t want it. They want their work to count, to pay enough so they can live with dignity and not hope for government largesse that can go away with a change in power. Like the expanded child tax credit that significantly reduced child poverty and hunger, as NPR reported when Congress allowed the program to close.

Anyone unhappy with the election who doesn’t address such terrible economic inequality — who assume that the big shift in voting by blacks and Hispanics was because they were all for white supremacy — doesn’t get the concept of household needs. Until they do, nothing will change. And voters will continue to put into office an Obama, then a Trump, then a Biden, a Trump, and however the circle continues because it’s easier for politicians to talk than to act responsibly and effectively.

Saying that a big chunk of people can't "make it" without Government money is an "opening" for an article on the difference between "today" and the days when people said that they'd "rather die and go to Hell, than" take a Government "wealth-transfer payment".

How many serious conflicts are fought by "dependents", against "the hand that feeds [them]?

Yes, kids "rebel" against the Rules that Mom & Dad establish. But, unless the "rebellious" kids are involved with some serious drugs, or something, Mom & Dad usually stay alive, and the grass stays mowed. But, the kids stay there and stay there (and might bring in someone else, also, to stay). And the costs keep rising, for Mom & Dad. But, the house stays THEIR castle, and it's THEY who get to make the Rules.

But, if the kids get a job and start saving money, it's not "rebellion", but "independent-mindedness". And the "goal" of "independent-mindedness" is, to move out, into one's own place, by the time one turns 18, and NEVER live under Mom's and Dad's roof, as a dependent, again. If that happens, there's peace and, even, mutual appreciation and -support.

And then, there's the "Waltons"-type situation, where there are at least two, adult generations, as well as the kids; and they have some means of "everybody contributes" to maintaining one roof and one boiler and one yard, instead of two; and the household survives the Depression with a LOT more options (and prosperity) than some others might have done.

So, HOW would those three PERSONAL "strategies for living" expressed, within the text of LEGISLATION whose aim was, to provide "incentives" to people, to participate in the "engineering" of "society" in a way that will "construct" a cultural "environment" that operates, essentially, as "a personal household WRIT LARGE"?

By reviewing the text of [budget] Legislation, IS IT POSSIBLE, to identify the sort(s) of [national and/or global] "household" that Legislators in different nations and/or localities seem to be trying to construct?

IS IT POSSIBLE, by doing so, to SHOW the ALREADY-EXISTING relationship between "Personal Economics" and [national or local] "PUBLIC POLICY"?

a) Which aspects of existing "public policy" look like efforts to establish or maintain ONE (or more) of the above-listed types of environment [i.e., "bread-disher-outer, and dependents" vs. "independent-mindedness/to-each-his-own" vs. "The {communitarian} Waltons"], into the future?

b) Which aspects of EXISTING "PUBLIC POLICY" look like efforts to move from one of the above-mentioned environment-types, to another?